[ad_1]

On the evening of October 11, 1984, Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, had her picture taken with a giant blue Teddy bear. It was the prize in a raffle at a gala being held at a club called Top Rank, in the resort town of Brighton, as part of the annual Conservative Party Conference. (Thatcher liked Teddy bears; she had two of her own, Humphrey and Mrs. Teddy, which she sometimes lent out for charitable events.) Thatcher, dressed in an evening gown with an enormous floral ruff, then returned to the Brighton Grand Hotel, where she and her husband, Denis, were staying, in Room 129-130—the Napoleon Suite. Denis went to sleep, but Thatcher, as was her habit, kept working, along with members of her staff. They were going over some papers related to the municipal affairs of Liverpool when, at 2:54 A.M., there was a boom, and then a crash. Plaster began to fall from the ceiling.

Five stories above them, in Room 629, Donald Maclean, the president of the Scottish Conservatives, and his wife, Muriel, were thrown out of their bed and through the air by the force of an explosion close by. He survived, but she died of her injuries weeks later. A bomb had been hidden behind a panel, under the bathtub, in Room 629, a spot that had been carefully chosen to compromise the hotel’s large Victorian chimney stack. In the seconds after the bomb detonated, the stack imploded, and was transformed into a funnel through which bricks, granite, and roof tiles rushed down, like a giant knife cutting through each floor.

A fifty-five-year-old woman in Room 628 was decapitated almost instantly. She was Jeanne Shattock, the wife of a local Party chairman. Three more guests were killed in the avalanche of masonry: in Room 528, Eric Taylor, another local official; in 428, Roberta Wakeham, the wife of the Tory chief whip; and, in 328, Sir Anthony Berry, the deputy chief whip. Berry had just returned from walking the two dogs he’d brought with him to Brighton. (Their barking would lead rescuers to Lady Sarah Berry, who was found beneath debris with a broken pelvis.) In Room 228, Norman Tebbit, Thatcher’s Secretary of State for Trade and Industry and a top hard-line lieutenant in her bitter confrontation with the miners’ union, was buried in rubble along with his wife, also named Margaret; they both survived, though she would be partly paralyzed.

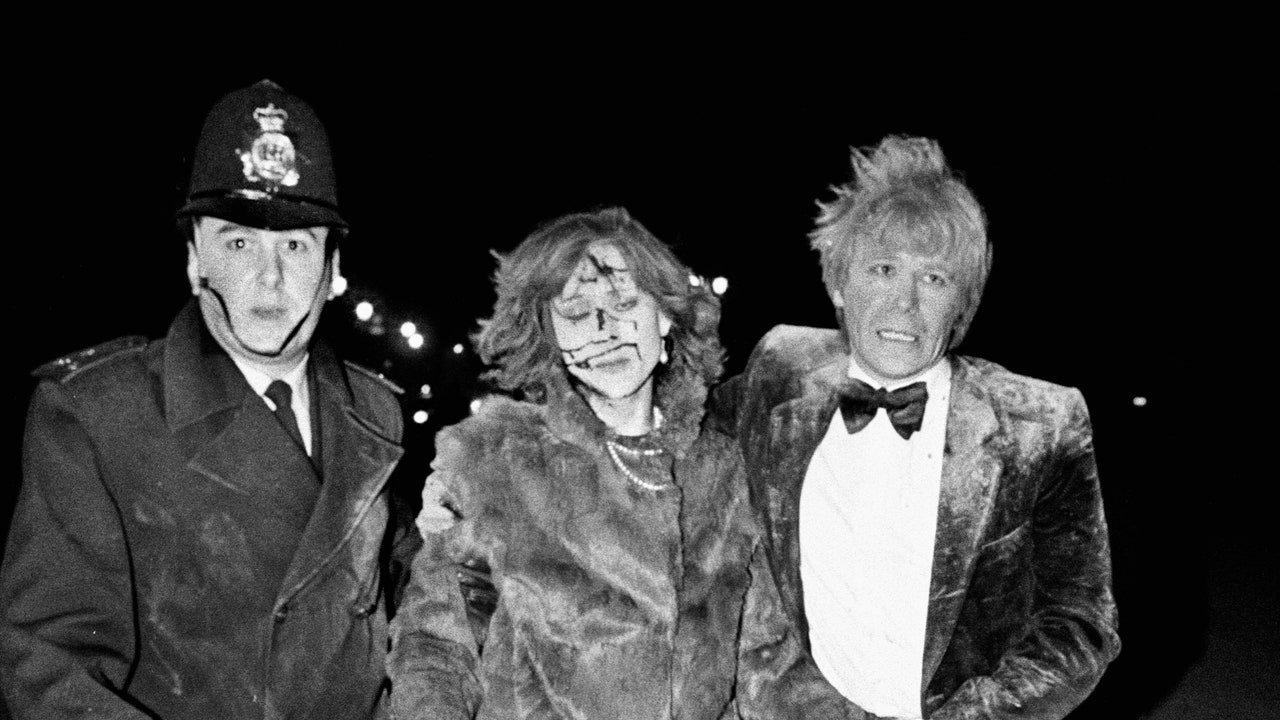

Had Thatcher been in the bathroom of the Napoleon Suite—and she was, two minutes before the bomb went off—there’s a good chance that she would have died. Instead, still in her evening dress, she got Denis out of bed and walked placidly from the room. The lobby was crowded with Tory grandees, some in dinner jackets and others in pajamas, many coated in dust. “I think that was an assassination attempt, don’t you?” Thatcher said. At that point, there was no clear picture of what had happened, or of whether there might be another bomb. But there were some guesses, as Rory Carroll, an Irish journalist, writes in “There Will Be Fire” (Putnam), a new account of the bombing. (In the U.K., the book is called “Killing Thatcher.”) When the Thatchers were put into a car to the Brighton police station, twenty minutes after the bomb went off, Denis, his hair uncombed, was already raging: “The I.R.A., those bastards!”

Carroll can’t quite believe that the Brighton bombing, “an attack that had almost wiped out the British government,” isn’t better commemorated, or more famous. He considers it, reasonably, to be “one of the great what-ifs” of modern history. There are multiple what-ifs built in. What if Thatcher, or other members of the Cabinet, had died? Pretty much all of them were there. Surviving, she had six more years in office, including the run-up to the first Gulf War. What if Norman Tebbit had stayed on the path he was on before the bombing and become, as was expected, Thatcher’s successor? Instead, he absented himself from electoral politics in order to care for his badly injured wife, and emerged, from the sidelines, as an increasingly shrill critic of the European Union, helping to drag the country to Brexit. Perhaps most provocative, what if the Provisional Irish Republican Army hadn’t chosen to go after the Prime Minister by blowing up a hotel filled with hundreds of people? What if it had forgone an armed struggle altogether? Decades later, the bombing still poses questions about terrorism, politics as violence, and the value of remembering (or of forgetting). The what-ifs persist because the significance of an event like this one isn’t fixed in the first moment; in Brighton’s case, the meaning is still being fashioned.

Ireland has no shortage of commemorations. Later this year, it will reach the end of what is officially known as the Decade of Centenaries. The Decade encompasses the 1916 Easter Rising, when armed nationalist groups briefly seized government buildings in Dublin, and the British Army responded with artillery shells and executions. But it also takes note of dates that are part of contrasting mythologies, such as the 1913 formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force by members of the unionist, or loyalist, community, many of whom were the Protestant descendants of Britons who settled in Catholic Ireland through the centuries; the 1921 partition; and the civil war that ushered in the establishment, in December, 1922, of the Irish Free State. (It became the Republic of Ireland in 1937.) Six majority-Protestant counties remained a part of the United Kingdom, and do so to this day, as Northern Ireland.

The Decade, as it unfolded, has stretched to a dozen years—history has a way of lingering—and so will overlap with yet another milestone, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the signing of the 1998 Good Friday, or Belfast, Agreement, on April 10th. The Agreement was a set of accords, between the U.K. and Ireland and between nationalist and unionist groups in Northern Ireland, including Sinn Féin, the political party then associated with the I.R.A. It brought to a close a particularly violent period known as the Troubles, and was only signed on Good Friday, a day after a deadline had expired, because negotiators kept on talking through the night, refusing to give up. (“We dare not let this opportunity pass because we won’t get another one like it in this generation,” a negotiator said, in the early-morning hours.) The deal is often cited as an example of how, every once in a while, supposedly intractable enmities can be put aside. President Joseph Biden, who was involved in the peace process as a senator, is expected to travel to Dublin and Belfast to celebrate.

Just in time for the anniversary, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Ursula von der Leyen, on behalf of the European Union, struck a deal—endorsed by Ireland—known as the Windsor Framework to resolve problems that Brexit created at the Irish border. The line dividing the Republic and the North is now also the land border between the U.K. and the E.U., of which Ireland remains a member. The deal is a second try, after the U.K. threatened to unilaterally break an earlier protocol it had agreed to, and involves checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the U.K. that might make it into the common market. Brexit itself has reopened questions about Northern Ireland’s dual identity—British and Irish—and, from another perspective, about the island’s incomplete unification.

“There Will Be Fire” is a reminder of just how much the Good Friday Agreement accomplished—how many fires it put out. What had been a civil-rights movement, protesting discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland, splintered and took a violent turn that accelerated after the Bloody Sunday of 1972, when British troops fired on a demonstration and killed fourteen people. Between 1977 and 1978, by one count, the I.R.A.’s bombing campaign included some six hundred attacks. Often enough, I.R.A. bombs killed ordinary Irish people—in one case, five cleaning ladies. The British government persisted with a response that was, by turns, indifferent, haphazard, or brutal. The level of collusion between government forces and the primarily Protestant unionist paramilitaries, who were waging their own terror campaign in Belfast, is still a matter of debate. Early in the book, Carroll, who is the Ireland correspondent for the Guardian, says that he intends to keep his focus on the Brighton bombing operation, without delving too much into matters such as “IRA attacks on Protestants in border areas, or loyalist targeting of random Catholics, or controversial security force killing.” To his credit, he doesn’t limit himself overmuch. It’s hard to render an episode in a centuries-old struggle as a caper story, but Carroll lets in just enough history to pull it off, mostly.

It helps that the Brighton case, seen as a police procedural, is quite something. In the wake of the bombing, investigators had no idea how long the explosives had been in the hotel or who, among the many I.R.A. members known and unknown to them, had planted them there. (Brighton was a popular spot for extramarital assignations, and a jarring number of people checked into the Grand Hotel under fake names.) Then someone remembered that, in a separate investigation, the police had stumbled upon a cache of weapons buried in a wooded area. In it were six timers, all set for twenty-four days, six hours, and thirty-six minutes. One seemed to be missing. When investigators counted back to see who had been in Room 629 twenty-four days before the bomb went off, they pulled a registration card in the name of Roy Walsh. No one at the London address he’d given had heard of him. It took more detective work to determine that Walsh’s real name was Patrick Magee, and still more—including a tense pursuit through Glasgow, vividly described by Carroll—to track him down.

As a young man living in Belfast in the early seventies, Magee had fallen in with the I.R.A., and had become a bomb-maker even before being further radicalized during a stay in the notorious Long Kesh prison. He was held there for more than two years without being charged, as part of a wildly ill-considered British program of mass detentions. He was, in short, one of the usual suspects; British authorities had nicknamed him the Chancer, because he took risks. It’s Carroll’s guess that he was given the high-profile Brighton job only because other, likelier candidates had been caught. Magee’s identifying mark was a missing fingertip on the pinkie of his right hand—a bomb-maker’s occupational hazard.

Thatcher’s main antagonist in Carroll’s narrative, though, is a different sort of operator: Gerry Adams, who was the head of Sinn Féin from 1983 until 2018. To this day, Adams denies that he was ever a member of the I.R.A., let alone complicit in any violent act, although he is widely known to have been a street-level commander and is believed to have sat on its governing Army Council. In later years, he developed an avuncular image; he, too, claimed to adore Teddy bears. Adams is often described as mysterious—Carroll calls him “sphinxlike”—but the puzzle is not whether he has lied about his past. It is about what he was really up to, and, as with the bombing campaign itself, what his lying has yielded.

Even before the Brighton bombing, Adams was apparently prodding the I.R.A. to pursue a political path alongside its armed struggle, a duality articulated by his ally Danny Morrison at a Sinn Féin conference in 1981: “Will anyone here object if with a ballot paper in this hand and an ArmaLite in this hand we take power in Ireland?” (An ArmaLite is an assault rifle.) Adams kept his hands hidden. His charade meant that, when the peace talks finally began, in the nineteen-nineties, others at the table could have some deniability about whether they were talking to a terrorist. It also meant that he escaped accountability for terrible acts that others had to reckon with. Patrick Radden Keefe, whose book “Say Nothing” explores Adams’s culpability in the murder of a widowed mother of ten, writes that, as “chilling” and “sociopathic” as he might be personally, “politically, it would be folly not to sympathize” with Adams’s long game. That is about where Carroll comes down, too.

[ad_2]