[ad_1]

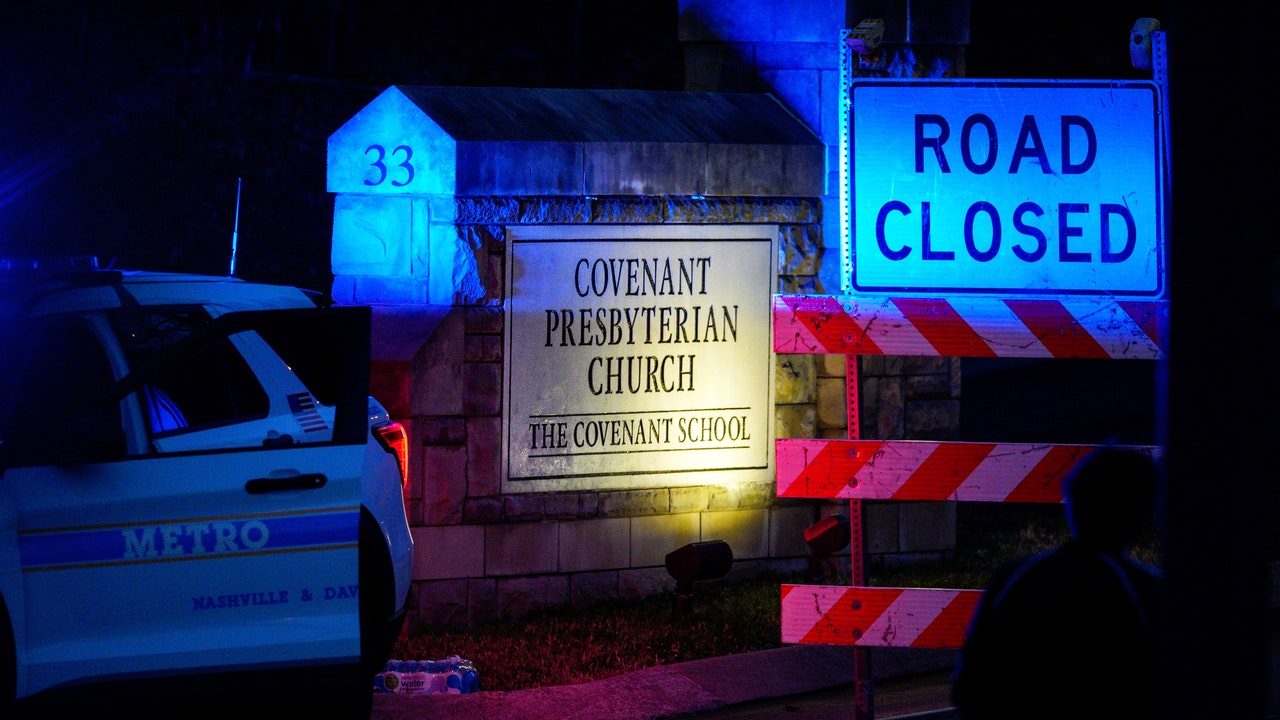

On Monday morning, a twenty-eight-year-old shooter, armed with three guns, all acquired legally, killed three adults and three children at the Covenant School in Nashville. It was the hundred and thirtieth mass shooting in the nation this year. Later that day, a Republican congressman from Tennessee, Tim Burchett, spoke with reporters about the tragedy in his home state. After expressing sorrow for the victims, Burchett said, of gun violence in the U.S., “We’re not gonna fix it—criminals are gonna be criminals.” There was, he believed, little action that lawmakers could take: “I don’t see any real role that we could do other than mess things up, honestly.” Instead of enacting legislation, he said, “we gotta change people’s hearts. . . . I think we really need a revival in this country.”

Burchett’s shruggy nihilism is a familiar Republican stance in the wake of mass shootings—a vaguely millenarian spin on weaponized incompetence. But then the conversation took an unexpected turn. A journalist mentioned that Burchett has a young daughter, and asked the congressman what more could be done to “protect people like your little girl” in school. “Well, we homeschool her,” Burchett replied, a bit dismissively. “But, you know, that’s our decision. Some people don’t have that option. . . . It just suited our needs much better.” The exchange ended there.

Is homeschooling the right decision for parents who wish for their children not to be shot dead at school? Does it suit their needs? The idea has been advanced before, notably by the conservative outlet the Federalist, which, following the mass shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, last year, ran an op-ed with the headline “Tragedies Like the Texas Shooting Make A Somber Case for Homeschooling”: “The same institutions that punish students for ‘misgendering’ people and hide curriculum from parents are simply not equipped to safeguard your children from harm.” Such accusations are drawn from the rhetoric of the conservative parents’-rights movement, which itself has its roots in the Christian homeschooling movement; these criticisms would likely not apply to Covenant, which is a Christian private school. But even if kids receiving a religious education are shielded from many of the dangers flagged by parents’-rights advocates—indoctrination by critical race theory, mandated gender confusion, reams of hardcore pornography crowding the school-library shelves—they still have to face the small but terrifying risk of their school becoming another Newtown, Parkland, Uvalde; they still have to participate in frightening active-shooter drills. Surely no such harm can reach a child behind the locked door of the family home.

School as a physical, social, political, or architectural concept—concepts that were tested by pandemic-era remote learning and that are perverted by school shootings—is premised on people coming together in a common space to receive a common education, one suited for creating a well-informed citizenry that is ready to participate in a democracy and share in the public good. The parents’-rights movement reacts to this necessarily messy and unpredictable schema with fear and attempts at control: of curriculum, of reading material, of time spent with teachers and peers of diverse views and backgrounds, of even the possibility of exposure to Michelangelo’s David. Within the logic of this movement, the parent with absolute command of her rights—the parent who protects her kids—is the parent who homeschools. She secures her private autonomy by withdrawing from the public good. She enshrines the conservative doctrines of personal responsibility and freedom from government interference through her actions in the domestic sphere. And, in Tennessee, she is permitted to do it with little more than a high-school diploma or G.E.D.—because a tenet of the parents’-rights movement is that “anyone can teach.” (Tennessee doesn’t even have particularly lax standards on homeschooling relative to the rest of the country. In several states, homeschooling parents don’t have to do a thing to prove that they are fulfilling their child’s constitutional right to an appropriate education.)

It is easy to sympathize with parents, regardless of their political or religious affinities, who might be tempted to retreat from the outside world, to hunker down, in a brutally divided country with more guns than people. (And there are many good reasons for a family to homeschool: a school may not be supportive of a child with disabilities, or of a child who faces bullies or discrimination.) But this sympathy for individual decision-making doesn’t accord with what we know more broadly about homeschooling—research has shown that homeschooled children are at higher risk for abuse and neglect, partly because they have less contact with mandated reporters such as teachers and social workers. Nor does this sympathy match what we know about gun violence. Eighty-five per cent of children ages twelve and under who are killed by a gun are shot in their own home. Almost two-thirds of child deaths involving domestic violence are caused by guns. Among children killed accidentally by firearms, the vast majority either shoot themselves or are shot by a peer, sibling, or parent, at their own home or at the home of a friend. Suicide deaths by children and teens, which typically involve a firearm kept in the home, have increased sixty-six per cent in the past decade.

It is home, not school, where guns pose the greatest risk to children. But, unlike school shootings, which can still sometimes stop us in our tracks, few of these stories will ever lead a news cycle. They are too terribly ordinary. Like many a homeschooled child, they are mostly invisible, unacknowledged, unaccounted for. For all our evangelical fervor, Americans are an oddly faithless lot in this matter: we believe only in what we can see. ♦

[ad_2]