[ad_1]

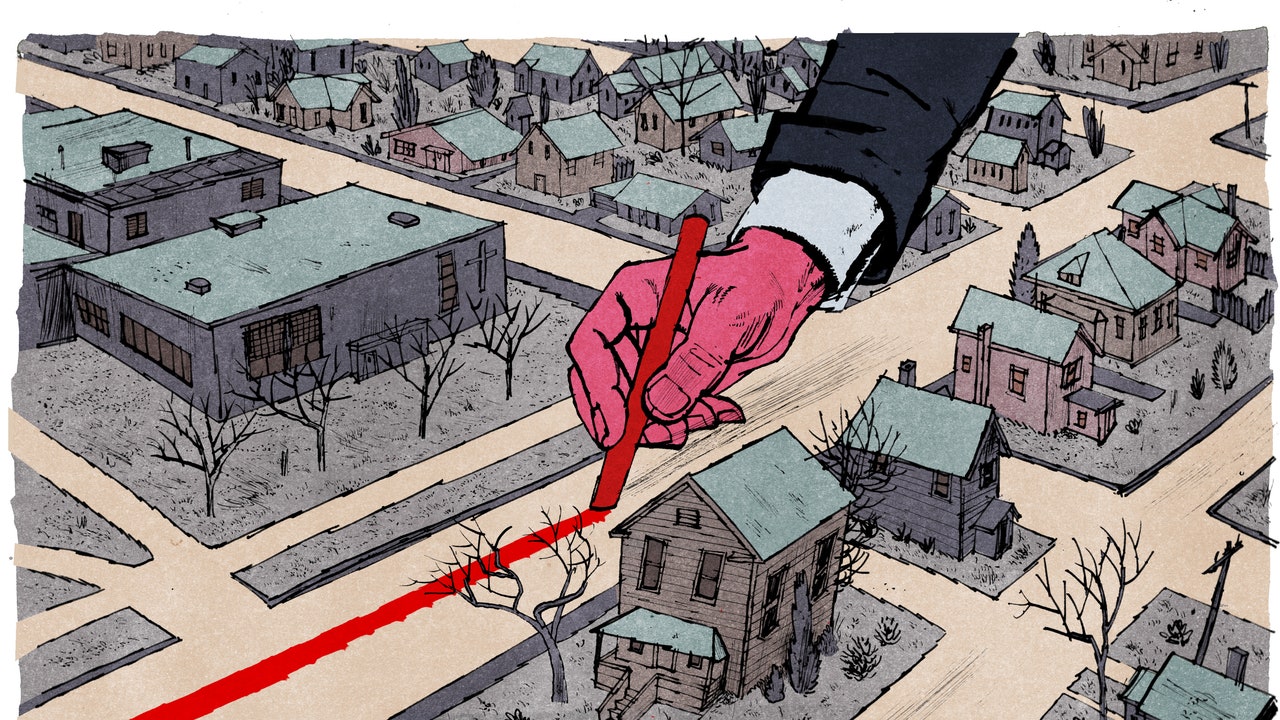

Last month, Mary Lynne Donohue drove me along Superior Avenue, a long artery that runs across Sheboygan, Wisconsin, a small industrial city on Lake Michigan. We headed west from the lake, passing expansive, stately homes that grew more modest the farther we got from the water. “You can see it’s exactly the same on both sides,” Donohue said, gesturing at the houses lining the street. In 2011, Republicans redrew the state’s district maps, using Superior Avenue to cleave the Twenty-sixth Assembly District, which for decades had encompassed the entire city—and had been reliably Democratic. The new map kept homes to the south of Superior in the Twenty-sixth, but put those to the north into the Twenty-seventh, which used to comprise the rural, Republican areas around Sheboygan. In every subsequent election, Republicans have won both the Twenty-sixth and the Twenty-seventh.

About halfway through town, Donohue, a retired attorney who is the president of Sheboygan’s school board, abruptly turned the car north, up a small side street, and slowed down in front of a brown, ranch-style house. In 2011, the house belonged to Mike Endsley, a Republican who, the previous year, had won the Twenty-sixth in an upset. The boundary line drawn by the Republicans had jagged up from Superior to keep Endsley’s house in the district.

Donohue parked, stood in front of the house, and shook her head. “In the high philosophy of redistricting, one of the basic goals is to keep communities together,” she said. Endsley retired almost a decade ago; now the two Assembly members and the state senator who represent the city all live in conservative hamlets outside it. Donohue went on, “When you cut municipalities in half, that municipality no longer has its own voice. It’s been taken away.”

The 2011 maps had been drawn in secret, in a locked wing of a law firm across the street from the Wisconsin state capitol. The year before, Republicans had captured all branches of the state’s government—a sweep carried out as part of REDMAP, a project promoted by Karl Rove to secure G.O.P. control of redistricting in swing states. After mapping dozens of possible scenarios, Republican legislative leaders settled on the most extreme partisan gerrymandering possible. Since then, they have never won fewer than sixty of the state’s ninety-nine Assembly seats, even when Democrats have won as much as fifty-three per cent of the aggregate statewide vote.

Donohue, who is seventy-three years old and has curly chestnut hair, grew up in Sheboygan. She has been a community-minded activist since high school, when she won the Young American Medal for Service, which L.B.J. put around her neck in a ceremony in Washington, D.C. After college, she and a friend took a ten-month trip across the country in a 1960 Volkswagen bus that they called the “flying tomato,” and then she applied to an auto-mechanics program at a technical college and to the University of Wisconsin Law School. She was rejected by the technical college but got accepted to law school. She eventually returned to Sheboygan to work on cases involving domestic-violence victims, tenant disputes, and disability benefits, among other things.

In 2015, Donohue and eleven other plaintiffs sued the state, alleging that the 2011 gerrymandering violated their constitutional rights. The plaintiffs won in federal court, scoring the first victory against partisan redistricting in three decades—until, on appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court threw out the case for lack of standing. (The Justices argued that plaintiffs were needed from each of Wisconsin’s ninety-nine Assembly districts.) “I started to cry,” Donohue said. “You felt a sense of hopelessness.” Nonetheless, in 2020, Donohue ran for the Twenty-sixth Assembly District seat. “I couldn’t leave it uncontested,” she told me. “It’s like not showing up on the battlefield.” She lost by eighteen points.

In 2021, the Republican-controlled state legislature and Tony Evers, Wisconsin’s Democratic governor, each proposed new maps, which are required by law every ten years. The Governor’s maps were based on models from a nonpartisan redistricting agency that he created. The Republicans reused the 2011 maps, with adjustments that minimized Democratic gains. A legal battle ensued, and, in November of that year, the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 4–3 conservative majority ruled, in a decision it described as “apolitical,” that the new maps should make the “least change” possible to the 2011 maps. In a dissent, Justice Rebecca Dallet called the ruling a “striking blow” to representative democracy in Wisconsin. The least-change approach, she wrote, “perpetuates the partisan agenda of politicians no longer in power.” Dallet noted that the least-change standard has no basis in the U.S. or Wisconsin constitutions. “I believe in the separation of powers,” Dallet told me, in her office in the state capitol. “In order for that to function, you have to be able to have people’s votes count; ‘one person, one vote’ has to mean something.”

Evers went on to draw new maps based on the least-change standard, but added a seventh, majority-Black Assembly district in Milwaukee to reflect the growth in the city’s Black population. Evers cited the need to satisfy Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits denying citizens equal access to the political process on the basis of race. The Wisconsin Supreme Court approved, with Justice Brian Hagedorn, a conservative, breaking from his colleagues to join the liberals. Republicans made an emergency appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that Evers’s new maps, which modestly diminished their advantage, amounted to a “21st century racial gerrymander.” The Court intervened through its so-called shadow docket—which is used to issue unsigned opinions without hearings or briefings—to reject Evers’s maps and rebuke Hagedorn’s opinion. (This has widely been interpreted as a signal that the Court is prepared to gut Section 2, the last remaining effective part of the Voting Rights Act.) The case was sent back to Wisconsin, where Hagedorn reversed himself and endorsed the original maps proposed by the Republicans, entrenching their control, in theory, in perpetuity. In the next election, Republicans won a veto-proof supermajority in the State Senate and came within two seats of one in the Assembly.

On April 4th, Wisconsin will hold an election to replace Justice Patience Roggensack, a retiring conservative, which could upend the Court’s ideological balance. Janet Protasiewicz, a circuit judge in Milwaukee, will face Daniel Kelly, a former state Supreme Court justice who was appointed by the former Republican governor Scott Walker, in 2016, to fill a vacancy. (In 2020, Kelly lost a bid for reëlection.) Already the most expensive judicial campaign in American history, the race is expected to cost more than forty million dollars, most of it spent by outside groups. (When Roggensack was elected, twenty years ago, outside spending totalled twenty-seven thousand dollars.) The outcome could reshape an institution that has helped transform Wisconsin into what the journalist David Daley calls a “democracy desert”—a place where voters stand little chance of effecting political change. In its most recent biannual report, the Electoral Integrity Project, which measures the democratic attributes of electoral systems, gave Wisconsin’s district maps twenty-three points out of a hundred, the worst rating of any state in the country. The score is on par with that of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The media tends to focus on the federal judiciary, and particularly the U.S. Supreme Court, but state courts handle more than ninety per cent of cases in the American judicial system. “The whole country was distracted, in some ways, by the successes of the Warren Court in the sixties,” Jeff Mandell, a co-founder of Law Forward, a nonprofit progressive law firm in Madison, told me. “You had organizations like the A.C.L.U. and others that were built up largely around going to federal court for relief. At some point, the right recognized that state courts can be much more powerful. Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction; they only hear certain kinds of cases. State courts can hear and decide anything. They also get a lot less attention, so they can radically change what’s happening in a state or region of the country.”

The U.S. is one of the only countries in the world to hold judicial elections, and these elections are increasingly dominated by dark-money groups. In 2014, the Republican State Leadership Committee launched a project called the Judicial Fairness Initiative, which focussed exclusively on winning state judicial elections. Last year, it backed winning conservative candidates for three Supreme Court seats in Ohio and one in North Carolina, flipping control of that Court in a change with enormous implications for abortion access and gerrymandering.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court has played a central role in an ongoing effort to overturn the state’s democratic norms. In 2015, the Court let stand one of the most restrictive voter-I.D. laws in the country. As a result, Wisconsin, which was once among the states where it was easiest to vote, is now ranked forty-seventh by the nonpartisan Cost of Voting Index. In a Facebook post, Todd Allbaugh, an aide to a Republican state senator, described a caucus meeting in which several Republican legislators were “giddy” over the voter-I.D. bill’s potential to suppress the votes of college students and minorities. Allbaugh quit the Party in protest.

That same year, the Court abruptly ended a criminal investigation regarding alleged coördination between Republicans and dark-money groups. It also issued an unprecedented order for prosecutors to destroy all the evidence that they had gathered. (A partial set of documents, leaked to the Guardian, revealed apparent quid-pro-quo payments, including seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars paid by the owner of a company that had manufactured lead paint to a conservative dark-money group in exchange for legislation granting legal immunity from lead-poisoning claims.) The conservative justices David Prosser and Michael Gableman refused to recuse themselves in the case, even though the groups being investigated had spent millions of dollars on their campaigns.

Since 2018, when Evers defeated Walker for the governorship, the Court has also played a decisive role in battles over the separation of powers. During the 2018 lame-duck session, the legislature stripped the governorship and the attorney general’s office (which had also been won by a Democrat) of significant powers. The legislature also effectively created its own attorney general’s office by giving itself the power to hire a special counsel, which it has used to file a bevy of lawsuits against Evers and other officials. In 2020, the Wisconsin Supreme Court overruled two lower-court opinions that said the lame-duck changes were unconstitutional.

More recently, the Court ruled that Fred Prehn, a Walker appointee to the board of the Department of Natural Resources, could stay on after his term expired, in May, 2021, until his replacement was confirmed—even though the legislature had refused to hold hearings on Evers’s nominee for the opening. Prehn’s extended tenure insured that the board remained under a 4–3 conservative majority. Text messages uncovered in an open-records request showed that Prehn coördinated the extension with Walker, industry lobbyists, and Republican legislators. “Senators are asking me to stay put because there [sic] not gonna confirm anyone,” Prehn wrote to a former D.N.R. warden. “So I might stick around for a while. See what shakes out. I’ll be like a turd in water up there.” During this time, Prehn cast the deciding vote to block groundwater standards for PFAS, also known as forever chemicals, which have been linked to cancer, liver damage, decreased fertility, and increased risk of asthma and thyroid disease.

[ad_2]